Tone Parallel

Issue 7 April 2023

In Tone Parallel, we have been following, albeit not entirely in chronological sequence, events in Duke Ellington’s life half a century ago. I had intended to write about The Third Sacred Concert in this issue but am going to save that for October, closer to the fiftieth anniversary of its one and only complete performance at Westminster Abbey and when the nights are drawing in anyway, the dying of the light chiming far more with the mood.

So, a brief detour and a stop at Disneyland instead.

This newsletter is being published on the eve of 11 April, fifty years to the day that Disneyland Line, Employee Newsletter, came out.

A week exactly prior to Disney’s epistle to its employers saw the light of day, 4 April, 1973, the San Mateo Times, California heralded the imminent arrival of Duke Ellington and his orchestra at Disneyland, reporting:

“Duke Ellington and his Orchestra will provide music for both listening and dancing pleasure from 8 pm to midnight pre-Easter,” Easter day falling on 22 April that year.

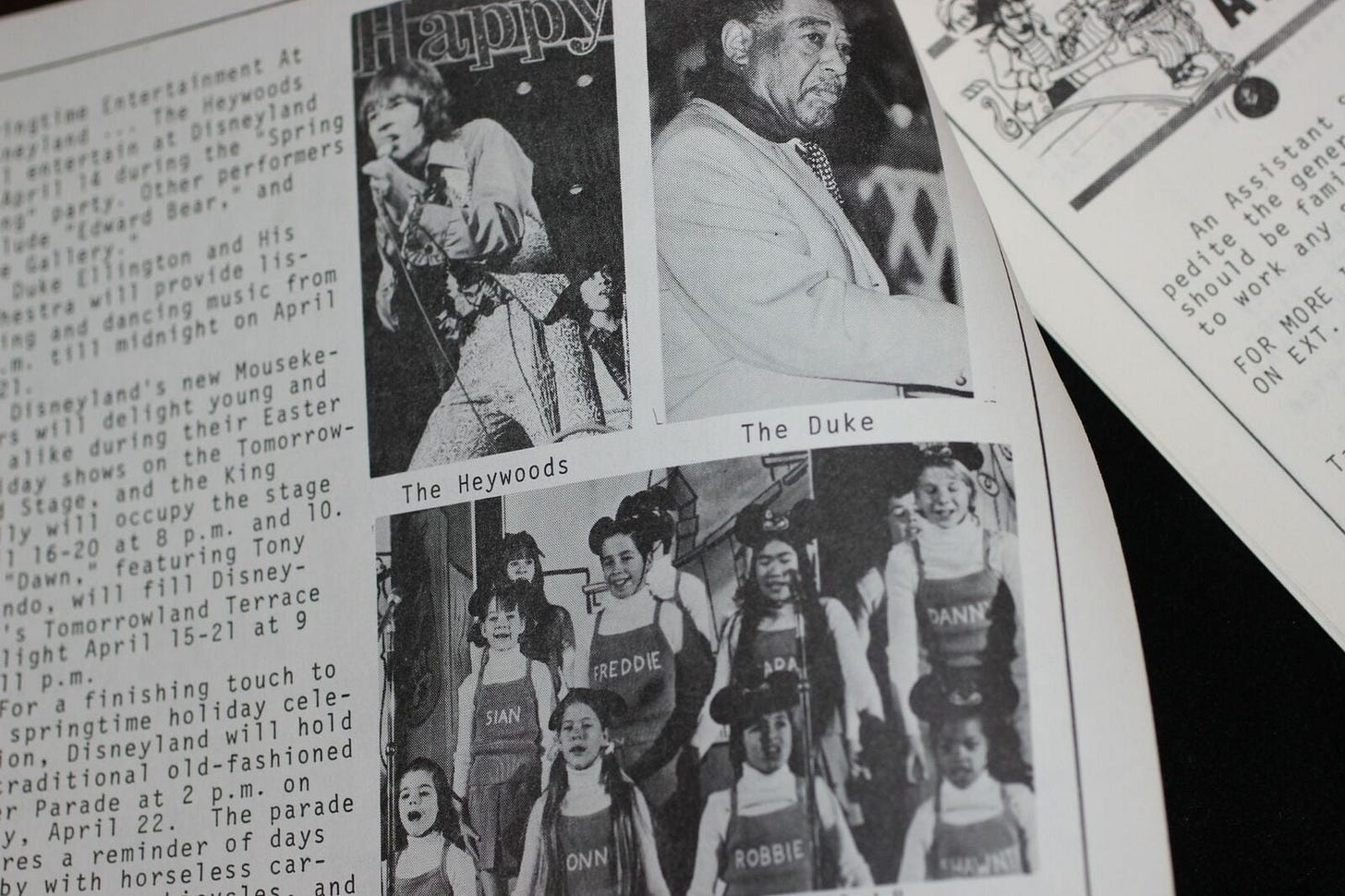

The engagement lasted from Monday 16 to Saturday 21 April. As the illustrations from Disneyland Line included here (courtesy of eBay) indicate, also on the bill were The Heywoods, The King Family and vocal group Dawn (comprising Telma Hopkins and Joyce Vincent Wilson) with Tony Orlando.

The company is no more surprising than those supporting acts who accompanied the Ellington Orchestra at the Royal Variety Performance six months later. But one might reasonably ask what on Earth were Duke Ellington and his orchestra doing appearing at an amusement park in the first place?

I wouldn’t say that Duke Ellington was a prophet without honour in his own country. The Pulitzer snub aside, Ellington was fêted frequently, particularly in the latter years of his life.

In terms of the Orchestra’s itinerary, however, the way Duke Ellington and his Orchestra were presented on television, the nature of the ‘crossover’ recording projects, there was a significant difference in emphasis in terms of the ways in which Ellington’s music was valued in Europe and in the USA.

Take, for example, the surviving telecasts we have of Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. It is to the UK and to continental Europe that we must look, by and large, for recordings of the full Orchestra live in concert. The Sacred Concert at Grace Cathedral aside, I am hard pressed to think of any video recording of a complete concert by the Orchestra in the USA. In contrast, we have recordings of full concerts by the full Orchestra in Paris, Brussels, Barcelona, Copenhagen and so on. In the USA, Ellington usually appeared on television alone, as a soloist or possibly with his rhythm section. When the full Orchestra appeared, it was usually at a studio set dance, and then as in January 1965, for example, as one in a series of ‘big bands’ which would include televised appearances also by the likes of Harry James or Charlie Barnet. In many ways, it was as if Ellington’s music survived only as a relic of ‘the swing era’, those years when popular music had caught up with and appropriated what Fletcher Henderson, Don Redman, Eddie Durham had been doing ten years earlier. Ever the chameleon, of course, Ellington anticipated, adapted, adopted that approach. That his music was so much more than the regimented ‘call and response’ of the dance bands before they rose to prominence and afterwards, nevertheless, it was within that pre-war time frame that his music continued to be perceived throughout virtually the rest of his career. The venues the Orchestra continued to play, long after the war and the flame of the big band era guttered reflected this categorisation, too – dance halls, campuses, air force bases. How else explain Ellington’s appearance at The Aquacade or his frequent sojourns in Disneyland?

In terms of audience’s differing responses to his music in the USA and Europe, Ellington was caught between a rock and a hard place. When the Orchestra arrived in Europe in 1933, Ellington was greeted as the creator of ‘a new reason for living’ in his music. Whenever he was perceived to have deviated from his ‘blues’ or ‘jazz’ roots, flirted with more popular material, the European cognoscenti were not slow to register their dismay and disapproval. And I think it is true to say also that what one can only really call deference to European forms of ‘serious’ music tended to colour the American response to Ellington’s forays into longer forms of music – the initial uncomprehending response to Black, Brown and Beige, for example. Worse, in projects which sought to ‘legitimize’ Ellington’s music, it seemed appropriate to slather it in strings. The most indifferent album in the Ellington catalogue for my money is Duke at Tanglewood. In what way dressing Ellington’s melodies in strings was some sort of fulfilling artistic statement escapes me

I can no more see what is to be gained by supplementing Black, Brown and Beige with strings either. Nevertheless, this is the project to which composer and orchestrator Randall Keith Horton devoted much of his professional career. His story is told in a book published last year by Karen S Barbera entitled Duke Ellington: The Notes the World Was Not Ready to Hear. Horton’s struggle to achieve this ambition and his involvement with performing Ellington’s Sacred music is outside the scope of this particular essay. I reviewed the book for Duke Ellington Society UK’s journal Blue Light (Volume 29, Number 1, Spring 2022) from which I shall quote the relevant lines directly.

The episode’s relevance to this particular essay is that it was during that engagement at Disneyland in April 1973 that Horton finally caught up with Ellington face to face. Of this encounter, I wrote in the review:

“Mr Horton rather makes himself sound like the successor to Billy Strayhorn in the Ellington firmament and this is to overegg the pudding somewhat. According to the book itself, it was in fact one of Horton’s compositions, Song For Jennifer, written for the composer’s sister, which the Ellington band performed during a residency at Disneyland in April 1973. Apart from attending the premier performance of Ellington’s Sacred Concert at Grace cathedral in 1965 as a member of the audience, the gig at Disneyland was Horton’s only direct encounter with Maestro. The episode ended in something of an unseemly wrangle over who was paying the hotel bill. While Horton’s involvement with Ellington could hardly be said to be on the same level as Billy Strayhorn’s, the episode must have given (Horton) some sense of why Strayhorn’s nickname for Ellington was ‘Monster’. In addition to the wrangle over the bill, with two hours’ notice, Ellington expected Horton to travel from San Francisco to The Anaheim Hotel, CA like a monarch summoning one of his subjects. It seems Horton was also dismissed quite summarily from court shortly after this episode.”

There are a number of very interesting ‘symphonic’ compositions, of course, where the instrumentation of the European symphony orchestra is deployed. I find it interesting to note that these longer pieces, written to be orchestrated by someone other than Ellington or Strayhorn, were generally composed at times when Ellington’s relationship to his orchestra was neither quite so close nor so organic – so the mid- fifties, for example with Night Creature when Strayhorn was largely absent, so too Johnny Hodges and Lawrence Brown. The early seventies is another example – so The River (though sketches for this by Ellington’s own orchestra were recorded, of course), Celebration, Three Black Kings – these pieces date from a period where the orchestra was subjected to a high turnover of personnel and Ellington’s work was not bespoke for his own aggregation.

It is ironic then, to me, to think that Randall Keith Horton should devote so much of his energy to trying to stage his ‘symphonisation’ of Black, Brown and Beige when his orchestration of Song For Jennifer, written with key players of the Orchestra in mind, has not, so far as I know, ever surfaced again. Horton’s account of preparing this composition for performance by the Orchestra at Disneyland is interesting and aspects of its inclusion in the Orchestra’s set really quite significant.

“I knew each band member and his unique style of playing,” Horton is quoted as saying on page 150 of Ms Barbera’s book. “I had seen them up close at the Great American Music Hall, dined with Mr (Russell) Procope in Sacramento, enjoyed the full band’s performance from backstage, read everything written about them in print and, of course, listened to the Ellington Orchestra’s recorded music for many years. The only unknown was a young French horn player who was a late addition to the following evening’s performance…. I wrote out each part meticulously; knowing exactly how it would sound at the hands of each musician and it all just flowed.”

According to Horton, Song For Jennifer was performed on what must have been the last night of the Orchestra’s residency, which was Saturday, 21 April. It is a shame that, according to the discographies, whilst the previous evening’s performance on Friday had been recorded, there seems to be no recording for the last night. The French horn player to whom Horton refers is listed in the discographies as Michael McGettigen. I must admit, this is a name that is new to me. It seems as though he was employed just for the duration of the Disneyland engagement, Ellington appearing to be without a third trombone chair during this period, exigencies to cover this including Johnny Coles doubling on flugelhorn in the brass section. McGettigan was just sixteen years old when he played with the Ellington Orchestra, having been at that time with the California Youth Symphony.

The photograph of Michael McGettigan included here, sad to say, was taken from his obituary page. McGettigan died in 2009 at 53 years old. Was he, I wonder, the youngest ever member of the Duke Ellington Orchestra? He may have been an obvious ‘dep’, being local as he was and a member of the California Youth Symphony but from here, the story becomes more complicated than that. It transpires that McGettigan was the son of Betty McGettigan who had been employed by Duke Ellington as his secretary in 1969. One assumes it was she who recommended her son for the engagement. Unfortunately, according to the composer, McGettigan’s contribution to the performance of Song For Jennifer was less than satisfactory. Horton writes:

“The only fly in the ointment was the performance of the young French horn player who had difficulties during the bridge. I tried to help him by singing his part, but it wasn’t perfect and it bothered me.”

To be fair, it was a bit of a tall order to expect a teenager to sight-read a new composition and with little rehearsal before the performance. Having found the name of the musician concerned and looked a little into his story, I hope this gives better context for Horton’s remarks.

It would appear – though I have yet to find evidence to confirm this claim – Michael McGettigan also played with the Orchestra after Duke’s death, under the direction of Mercer Ellington. Betty McGettigan’s story subsequently is rather enmeshed with the long weeds of the years immediately following Duke Ellington’s death, involving litigation over the libretto for one of Ellington’s final works, Queenie Pie. We shall return to this work and Betty McGettigan’s involvement next year.

Ahead of publication for The Notes the World Was Not Ready to Hear, I ‘reached out’, to use the modern parlance, to its author Karen S Barbera simply via message on Facebook but received no response. It is equally impossible to find a way of connecting with Horton himself. Like Ms Barbera, a trawl of social media – Facebook, Twitter, Instagram – results only in a mildly disconcerting and disappointing trail of lapsed websites, empty social media accounts and dead ends. I hope one day that this ‘lost’ chart for the Ellington Orchestra – possibly one of the last non-Sacred pieces arranged specifically for the band of 1973 and therefore Duke Ellington and his Orchestra’s final iteration – might turn up and be played again by one of the several repertory orchestras that specialise in Ellington’s music ‘live’.

During the brief Keith Randall Horton ‘era’ whilst Ellington was in residence at Disneyland, he was working on the music for the Third Sacred Concert. We shall turn our attention to the première and only performance in full of this work in the next Tone Parallel and in an autumn more appropriate.