Tone Parallel

Issue 6 March 2023

Vaudeville is the Place, Man

During the celebrations for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee in the summer of 2022, reference was frequently made to her meeting with Duke Ellington at the Leeds Festival in 1958. That occasion marked also twenty-five years since Ellington’s first visit to the UK.

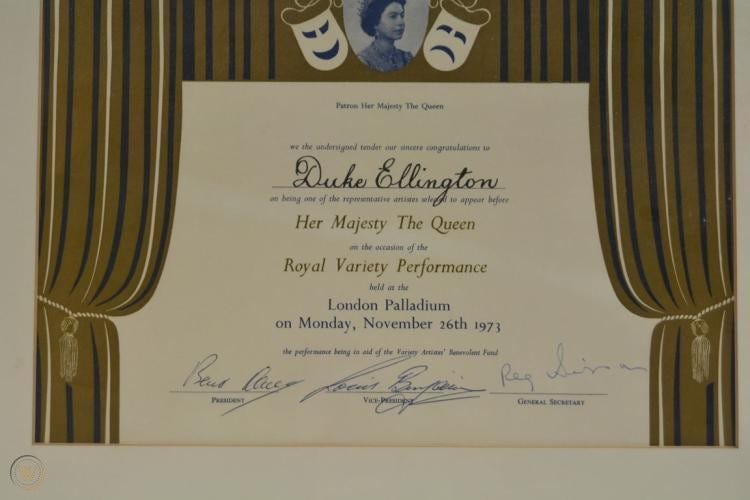

Less well known is the encounter pictured in the photograph that headlines this essay. Here, Ellington has a brief audience with Her Majesty following his Orchestra’s appearance in The Royal Variety Performance which took place on 26 November 1973, the second leg of Ellington’s tour of the UK that winter following his return the previous day from Africa where the itinerary had included an audience with Emperor Halle Selassie at the Jubilee Palace in Addis Ababa.

The performance was recorded for ATV, a station based in the Midlands that was part of the Independent Television Network and broadcast on Sunday, 2 December 1973.

The website The Royal Variety Charity contains the following account of the evening:

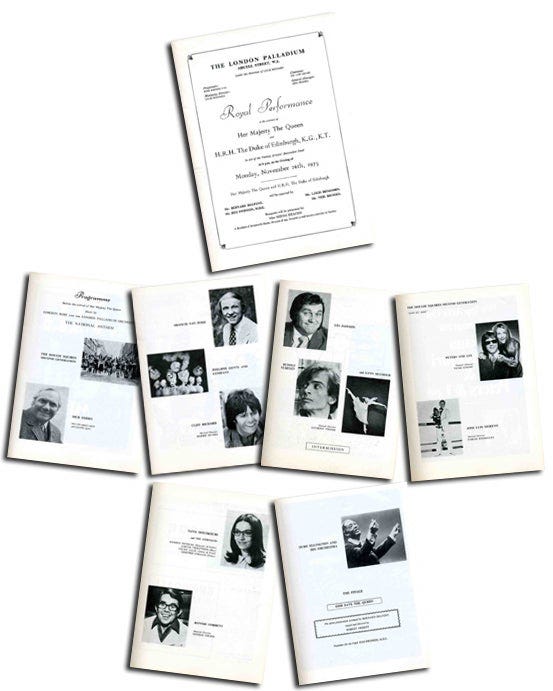

“To 1973 belongs one of the most frequently told stories of the Royal Variety Show, centred on the big name of the night, Duke Ellington. Due to yet another travel mix-up, this time en-route from Kenya, he and his musicians arrived after the rehearsals, with only an hour and a half to go before curtain up. While some of his musicians went to the theatre to take notes from Robert Nesbitt (the producer of the show) and find out what they were supposed to be doing, Duke Ellington, who was not young by that stage, retired to be bed exhausted. To add to the mounting chaos the band's musical instruments were still sitting in the customs area at Heathrow! Tahoe show had been running a nail-biting 15 minutes before the instruments and band clothes finally arrived. It wasn't until the interval that Robert Nesbitt actually saw Duke Ellington, lying stretched out in his dressing room in the dark. They went through the details of his entry through the curtain before the band was revealed.

When it came to what they were going to play, the director was happy to leave it to Ellington to decide. His only advice was that the Duke of Edinburgh's favourite tune was I'll Take the A Train (sic). Bearing in mind that he was talking to someone who hadn't even been able to set foot on the stage it was pretty nerve-racking.

Great artiste that he was, Ellington carried it off perfectly; stepping through the curtain to take his bow, he turned round and as the curtains opened to reveal his musicians he went straight into I'll Take the A Train, (sic) which was a great way to start.”

The Royal Variety Performance was an annual event for charity. The first ‘royal shows’ as The Royal Variety performance was originally called were attended in 1912 and 1919 by His Majesty King George V and Her Majesty Queen Mary who became subsequently Patrons of the Royal Variety Charity from 1921.

As the name ‘Variety’ suggests, the bill consisted of an assortment of popular entertainers of the day, musicians, singers and comics. The company on this occasion, for example, included such comedians hugely popular with British audiences such as Les Dawson and Dick Emery who, seventy years earlier and more would have been quite at home in the Music Hall or as it was often termed the Palace of Varieties. This was a venerable theatrical tradition, the British equivalent of what Ellington and his fellow Americans would be more likely to term Vaudeville.

This televised Variety performance was part of what proved to be Ellington’s final visit to the United Kingdom, some forty years on from his first visit in 1933. There is a certain symmetry in the fact that during their first tour also, Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra appeared at the same venue in which the Royal Variety Performance was recorded, The London Palladium. To categorise this performance as ‘Variety’ strikes an even more profound echo with Ellington’s inaugural visit to British shores, however. Indeed, having experimented with a format called Crazy Evening where the Palladium played host to a troupe of British comedians known as The Crazy Gang, the management of The London Palladium revived the Vaudeville tradition for Ellington’s arrival. He appeared as ‘top of the bill’, headlining thirteen acts, nine of which consisted of assorted acrobats, jugglers, dancers, tumblers and comics.

Ellington’s antipathy to the concept of ‘categorisation’ is documented well. History does not record how he felt about his music being bracketed with ‘Variety’, a categorisation that was only re-affirmed by the British Broadcasting Corporation which in transmitting Ellington’s first performance on the ‘wireless’ (14 June 1933), broadcast the Famous Orchestra between 8.00pm and 8.45pm on the National Service, the prime time slot for music hall and variety entertainment within the corporation’s output.

This point is made by Professor Tim Wall in his fascinating essay Duke Ellington, the meaning of jazz and the BBC in the 1930s (in New Jazz Conceptions History, Theory, Practice Edited by Roger Fagge and Nicolas Pillai). Professor Wall writes:

“Although Ellington and his band had developed their music in a very different kind of establishment, The Cotton Club Black and Tan, in the UK the band’s main performances took place in the fading grandeur of the best-known British music hall, the Palladium. By programming Ellington in its own ‘music hall’ slot, the BBC not only positioned his music as a particular form of entertainment, it drew on a whole set of institutionalised assumptions about what his music meant and how it would be presented and heard.”

As Professor Wall explains in the course of his essay, Ellington’s music was categorised by the BBC in different ways at different times. When his gramophone recordings were played by the BBC in the mid-30s, for example, they were anthologised with excerpts from symphonic pieces and folk music of the sort frequently categorised these days as ‘world music’. The purpose of these anthologies, according to the listings magazine radio Times was ‘to convince jazz enthusiasts that serious music can be “rhythmic”, too’ in order ‘to show development of rhythm from the music of the West African negroes to that of Stravinsky’. This perspective on Ellington’s music accorded with the approach Irving Mills took in promoting Ellington’s genius and there is a parallel too, perhaps, in how Ellington viewed his own work as it evolved into the longer form pieces which characterised his work to the end of his life.

Again, perceptions changed with the transatlantic wire broadcasts by the BBC as the thirties became the forties and the America Dances programmes. During this period of the so-called ‘Swing Era’, Ellington’s music was now primarily identified with the dance band music of the likes of Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey or Artie Shaw, overshadowing the rather higher brow perceptions of Ellington’s work which had existed heretofore. As Professor wall says:

“The idea of big band dance music, primarily created for dancing, overshadowed the earlier sense of Ellington as a progressive, trans- genre musical genius championed by the BBC.”

The irony in all this is that to Ellington, these descriptors were irrelevant. As an artist unconstrained by labels or boundaries, he simply moved ‘ever onward and upward’ in the words of his arranging and writing companion, his favourite composition being “the next one”, creating the sort of music he wished to create ‘beyond category’.

In an arresting synchronism, as I was planning this essay, I happened across a video on YouTube of the Danish documentary from 1969 Portraet Af En Hertug. Ellington is interviewed and says at one point:

“We don’t encounter an audience as a jazz audience I don’t think… we have a rather wide range of tonal character and we don’t get a chance to discriminate to decide who is what.

We go into areas for instance where people don’t know anything about the word jazz. …We’ve been to the Far East and you’re playing in a ballpark to six thousand people. Well, in a country in the far east where you have billions of people a very, very tiny percentage of them have even heard of the word jazz or know anything about it and so we can’t depend on the word. We can’t depend upon anything. You just have to go out and do a performance and if the performance believable they respond; if it’s acrobatic they respond; if it’s sensuous they respond and that’s all we can depend upon. The name doesn’t mean anything. It’s all in how believable or how sensitive the aura or presentation and if it’s agreeable to the ear, then you are very fortunate and then you are together. You know, when we say your pulse and my pulse are together, we’re swinging which is total agreement.”

To return to the topic of Ellington’s appearance at The Royal Variety Performance in 1973, and to contemplate, however briefly, the label ‘jazz’, I consider there were only two ‘jazz’ performers who could make an appearance in that context at that venue, in front of that audience on television in 1973. Certainly, there were homegrown ‘jazz’ acts whose names would be familiar to UK readers – acts such as Kenny Ball and his Jazzmen or Acker Bilk or Syd Lawrence and his Orchestra. These would be ‘name’ acts largely familiar to British audiences. They are not acts, however, that could appear, as Ellington did, ‘top of the bill’ and indeed it is rather bathetic to mention them in the same breath as Ellington. No, the ‘jazz’ performers who could carry off that evening’s entertainment were Duke Ellington or the man who had also first visited Britain to perform in the early thirties, Louis Armstrong.

Of course, Armstrong was dead by 1973 so that left Duke alone to carry the torch for ‘jazz’ bridging the divide between ‘entertainment’ and ‘art’, ‘jazz’ and what passed for popular music in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Equally adept at reaching wide mainstream audiences, nevertheless, back in the day broadcasters did discriminate between the kinds of ‘jazz’ Armstrong and Ellington respectively offered. From Professor Wall’s study again:

“Put succinctly, Armstrong was increasingly taken to represent the notion that jazz was a folk music which needed to be understood through its origins, while Ellington was constructed as a modernist, and jazz as a new art form. These two new discourses became the dominant perspectives of British jazz fans. … within the BBC a third trajectory is apparent, in which the early elements of jazz form were incorporated into the BBC’s idea of light musical comedy, which itself would form the basis of the later idea of light entertainment.”

‘Light entertainment’ is the quintessence of the fayre offered by The Royal Variety Performance so the inclusion of a tribute to Louis Armstrong which had become a feature of Ellington’s performances at that time could hardly be more appropriate. There is an echo, too, of Armstrong and Ellington’s original first tours of the UK in the thirties.

More an impression than an impersonation, the inclusion of a tribute to Armstrong by way of a turn singing and playing by trumpeter Money Johnson first seems to have been a feature of Ellington’s late performances from the European tour of 1971, Armstrong having passed away some three months or so earlier. In fact, at a cursory glance – and, of course, more thorough research would be needed to verify this – the earliest surviving instance of a performance of Money Johnson’s Armstrong tribute from which a recording is known is the second house, 20 October, 1971, The Winter Gardens, Bournemouth, the subject, coincidentally, of the first Tone Parallel newsletter.

Johnson’s tribute consisted of a trumpet solo and Armstrong-style vocal chorus of Hello, Dolly and/ or Basin Street Blues. For the night of the Royal Variety Performance, Basin Street Blues was chosen.

Spencer Williams’ composition was recorded by Armstrong in the year it was written, 1928. I first encountered the tune at eight years old when my father brought home an LP of the soundtrack from The Glenn Miller Story where, on side 2, the number was a feature for Armstrong and The All Stars. Its inclusion in the Miller bio-pic is appropriate since Miller himself, in collaboration with Jack Teagarden, added the additional ‘Won’t you come along with me…’ lyrics for a recording made a little over two years after Armstrong’s original by The Charleston Chasers on 9 February 1931. Ironically, if memory serves correctly, Armstrong did not deliver this opening verse in his performance in The Glenn Miller Story.

Armstrong’s imprimatur possibly conveyed an authenticity to the composition which it did not altogether deserve. Perhaps because of the later augmentations by Miller and Teagarden; perhaps because it so obviously tries to aspire to the work of WC Handy (though written a good ten years or more after Handy’s own Beale Street Blues) I’ve never really considered it the ‘genuine article’ in the way Handy’s blues work was. This, however, is possibly to play the game of categorisation the broadcasters indulged in, labelling, categorising quite meaninglessly about music, the true rich complexity of which cannot so easily be pinned down. It is as patronising as the BBC discriminating between Armstrong and Ellington, the latter, in Tim Wall’s phrase, “a sign of a progression within jazz towards Stravinsky-like sophistication and advancement,” the former, a purveyor “of primitive jazz rhythms.” All these nice distinctions take flight when Ellington invites Money Johnson to the microphone to fulfil his own solo responsibilities.

Johnson’s Armstrong-inspired turn was not always appreciated, however. Writing about a performance by the orchestra in Preston, Lancashire which took place on 30 November, 1973, journalist Peter Gardner called Johnson’s performance “a low point’. He wrote: “Trumpeter Harold ‘Money’ Johnson gave us an Armstrong-like version of Hello Dolly, which wasn’t terribly good. It was part of the concert where a jocular Ellington predicted what music would be around in the coming centuries. I have never fathomed why the Duke himself or anyone who played with him needed to move outside the Ellington-Strayhorn songbook for inspirational material. And predicting what future generations would be listening to seemed an ideal opportunity to be optimistic and play something Ellingtonian.”

As Gardner notes, Ellington’s preamble (well-rehearsed, tried and tested in the manner of the patter he always used to introduce , say, The Tattooed Bride or Harlem). Ellington’s routine will be familiar to any aficionado who owns a copy of the Eastbourne Performance album. He introduces Johnson’s routine on the stage of the London Palladium with:

“Little Money Johnson, ladies and gentlemen, will now come forward and give you an example of what the music styling will really be one hundred years from today. One hundred years from today in this computerized, air-conditioned, prefabricated plastic jungle. Money Johnson. The future. Tonight. The Palladium.”

Discordant piano notes, jangling rhythm section, the bestial howl of Chuck Connors’ bass trombone, summoning the spirit, perhaps, of some nihilistic vision of a dystopian future in the form of a sort of unspeakable congress between the fringes of free jazz and heavy metal, met with laughter from the audience, prefaces a sudden sunburst of the much more familiar and comfortable trumpet style of Louis Armstrong as Money Johnson launches into Basin Street Blues.

https://ellingtonlive.blogspot.com/2023/02/vaudeville-is-place-man.html

The performance may not have thrilled hardcore Ellington aficionados but applying Duke’s definition of luck as “doing the right thing at the right time in front of the right people’, in this setting, the choice of number was spot on and received warmly.

Indeed, the entire set, the ‘top of the bill’, which ran a little under a quarter of an hour, demonstrated Ellington’s popular touch, his unerring sense of audience and occasion. Opening with the last really ‘popular’ success he had enjoyed, Satin Doll, Money Johnson’s turn was the centrepiece of the presentation followed by an abbreviated medley of greatest hits and the contemporary number One More Time For The People which gave the opportunity to showcase singers Anita Moore and Toney Watkins (the latter having been booed off the Berlin stage only two weeks previously but “all the kids in the ballet” as Ellington described him received with much more good humour here) and thereby the entire company as the set reached its crescendo. It was a bouquet not only of Ellington’s greatest hits in terms of music but also his showman’s patter, everything from “Everybody look handsome” to “We do love you madly,” delivered in a long list of languages prepared for him by his secretary Patricia Willard, learned by heart and intoned by Ellington.

The fifteen minutes of Famous Orchestra was a terrarium, a hothouse in miniature for Ellington’s most exquisite blooms.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second was not the only person in the room who was monarch of all she surveyed. Here was Edward Kennedy Ellington, citizen of the world presenting his music one more time, truly, for the people.

For the people. One more time.

My thanks to Ulf Lundin, Duke Ellington Society of Sweden, for his help with video research.