A PROCLAMATION

WHEREAS, his life is devoted to serving mankind through music;

WHEREAS because of his untiring ceaseless search for quality and unflagging quest for the best in man, he serves art and humanity at once;

WHEREAS, his compositions have permanently enhanced the world’s musical repertoire;

WHEREAS, in our time, he is unique, as the world’s most honoured musician;

WHEREAS, his name alone is synonymous with the cultural core of 20th century American music;

WHEREAS America has gone wherever he has gone and America and its music are better understood and more loved wherever he has been;

WHEREAS, he continues to enrich the lives of the citizens of Wisconsin, America, indeed the world;

NOW, THEREFORE, I PATRICK J. LUCEY, Governor of the State of Wisconsin do hereby proclaim July 17-21, 1972 as

DUKE ELLINGTON WEEK

In the state of Wisconsin IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Great Seal of the state of Wisconsin to be affixed, Done at the Capitol in the City of Madison, this thirtieth day of June in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and seventy-two

By the Governor:

ROBERT ZIMMERMAN PATRICK LUCEY

Secretary of State GOVERNOR

This rather grand edict graced the inside front cover of the programme for the Duke Ellington Festival hosted by the University of Wisconsin in the summer of 1972. The decree from Patrick Lucey, Governor of Wisconsin, transmogrified the festival of concerts and workshops into an entire Week honouring Duke Ellington and his works.

In addition to the grandiloquent assertions expressed by the Governor, a rather more prosaic note was also included at the foot of the inside cover which read as follows:

Use of Flashbulbs or Lights by Photographers is not Allowed During the Concerts. Picture taking is permissible Only With Available Light. Persons photographing Dr. Ellington At Any Time are Requested Not To Use Flashbulbs Within 8 Feet of His Eyes – On Request Of His Physician. Thank You.

Ellington was notorious for indulging his health, lying in repose on a couch wrapped in his robe with a damp towel across his eyes in his dressing room between sets, for example. His concern about his health extended to having his own physician in his entourage and it was no doubt at the insistence of his medic, Dr. Arthur Logan that the structures were laid down with regard to photographing Maestro.

As discussed in the previous edition of Tone Parallel, however, by the time he got to Wisconsin, Ellington’s health was indeed compromised severely and the bronchial issues that would eventually claim his life were present.

Whether Ellington’s deteriorating health was responsible for the uncharacteristic outburst of temper which occurred during Duke Ellington Week can only remain idle speculation. The object of his ire was tenor player Paul Gonsalves.

In his superb blog No Sound Left Behind, Matt Lavelle describes the incident:

“Two years before they left this world, Duke Ellington and Paul Gonsalves were at the University of Wisconsin. At some point… Paul had not arrived for something important and was publicly cursed out and dressed down by Duke. It was out of character and delivered on a level that people had never seen before.”

One eyewitness to this dressing down was composer and pianist Anthony Coleman

“He called Paul Gonsalves an a –,” he recalled. “Gonsalves was just so drunk and lost. The room froze.”

There was a payoff to this incident, however, which was without doubt the most luminous and transcendent moment to emerge from Wisconsin’s Duke Ellington Festival.

As Anthony Coleman explained: “The next day, at a lecture Duke was giving, Paul showed up looking bleary, like he’d taken 10 showers. He interrupted the lecture and said, ‘Duke, I want to play Happy Reunion with you.’ It was very intense, very beautiful.”

I had the pleasure recently of speaking directly with another Ellington admirer who attended much of the Duke Ellington Festival and was there when the reconciliation and performance of Happy Reunion took place.

Chuck Nessa is the well renowned and much respected producer of Nessa Records which he founded in 1967 at the urging of Roscoe Mitchell and Lester Bowie whose music, Chuck has said, defines his professional career. Previously Chuck had worked in record stores (notably The Jazz Record Mart where he worked for Bob Koester and learned how to be a producer through his work for Delmark Records). Chuck had previously come closest to Ellington’s orbit through his interest in producing Randy Weston’s album Berkshire Blues when Chuck through which Chuck came into contact with Ellington’s sister, Ruth.

It was the music of Duke Ellington that was the gateway into jazz for Chuck and an album his father brought to his attention, expecting to hear it once a week. Chuck told me that the album in question, Piano in the Background “alerted me to jazz. I didn’t know that my father ever heard music and it turns out that before I was born he and my mother went to ballrooms all over Iowa catching the big bands so Ellington was my introduction… When I first went to a record store I discovered that it was in a section called jazz and everything was there. I bought a Louis Armstrong Hot Five record because it was jazz. I didn’t differentiate the eras. I was listening to Sonny Rollins and to Johnny Dodds. It was just a very broad spectrum I was introduced to.”

It’s entirely appropriate then that Chuck’s father should be there when Duke Ellington rang inviting Chuck to attend the festival at UWIS. By this time, Chuck had already been producing records and was working in Discount records, a store on State Street in Wisconsin. While they were in town, members of the Orchestra would visit the store frequently. “They were looking for cassettes. Gisele Minerve was there and I forget who else but there were a half dozen guys in and out of the store.” Owing to his work in the record store, Chuck was in a position to know that album Latin American Suite was to be issued imminently. Chuck told me “When I first asked (Ellington) if he had any of the Latin American Suite in the book and he said no he didn’t know that the record was coming out; that they didn’t give him a heads up so none of the material was at hand.”

Indeed Chuck’s reputation as record store manager and record producer had preceded him, however and the night Ellington phoned, “My parents were visiting. We had a two-year-old son and my parents were visiting us for the week and we were sitting down to eat dinner (when) the phone rang. My father reached over and answered the phone and looked at me and said, ‘Duke Ellington wants to speak to you.’ I quickly went into the bedroom where we had another phone and I could talk and it was actually Stanley Dance on the phone who said that Duke Ellington wanted to talk to me. Dance knew who I was because we had never met but he was a record reviewer. He was on my mailing list and he got my records when they came out. He put Duke on the phone and Duke asked me if I had tickets for everything. I said, ‘No, not yet,’ and he said, ‘There’ll be your name at the door for every event just show up and tell them to give you tickets and how many will be in your party.’ I said ‘My wife and I,’ and he said, ‘OK fine,’ and so that’s how I got in to all these things.”

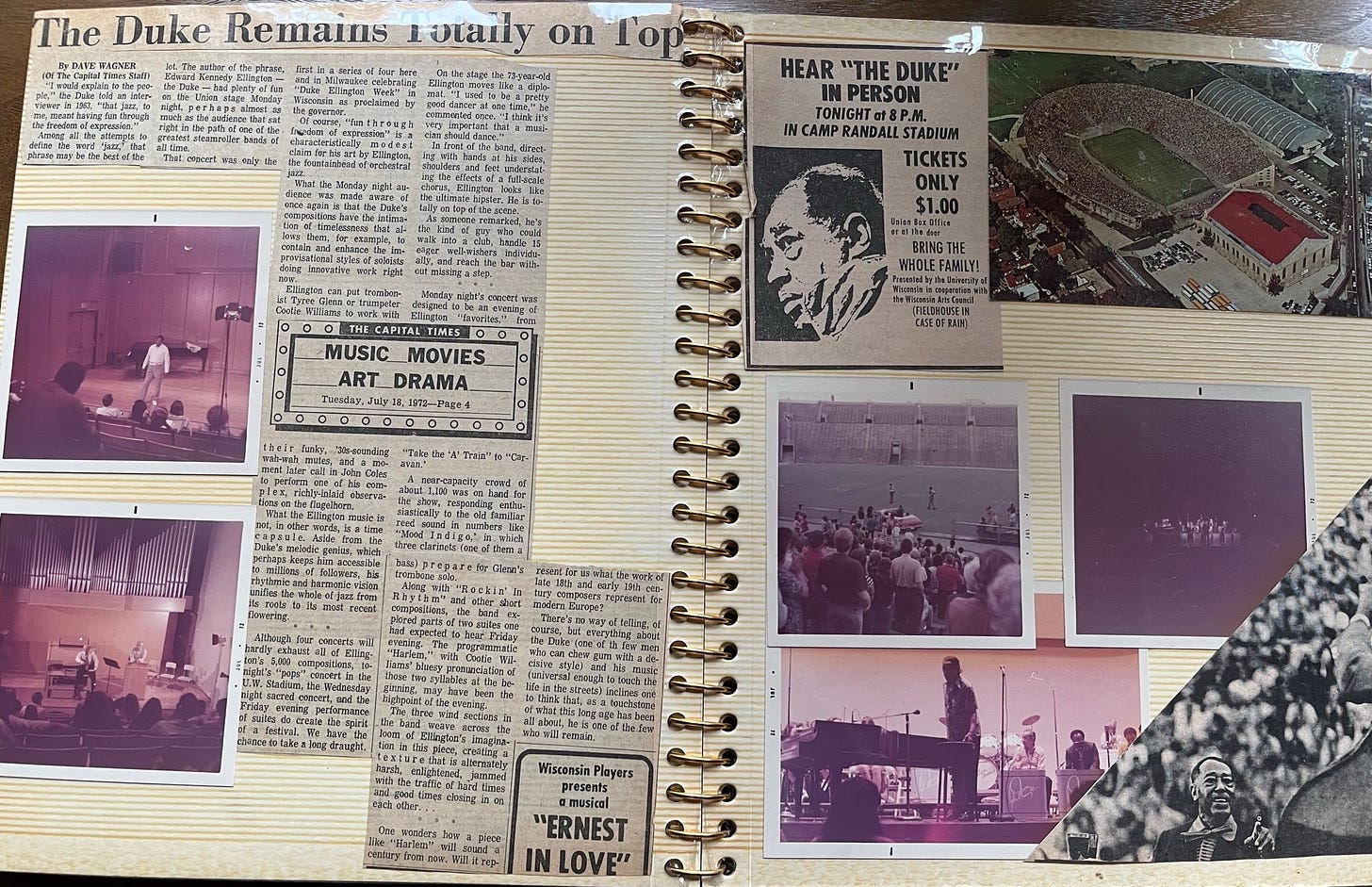

Reminiscing about the Duke Ellington Festival fifty years after the event, Chuck said, “When I first heard about it I couldn’t believe it would happen. You know there was just the whole week. In a way it was a musical blur music coming at you and the excitement and after all these years, it’s hard to recall any specific things about it.

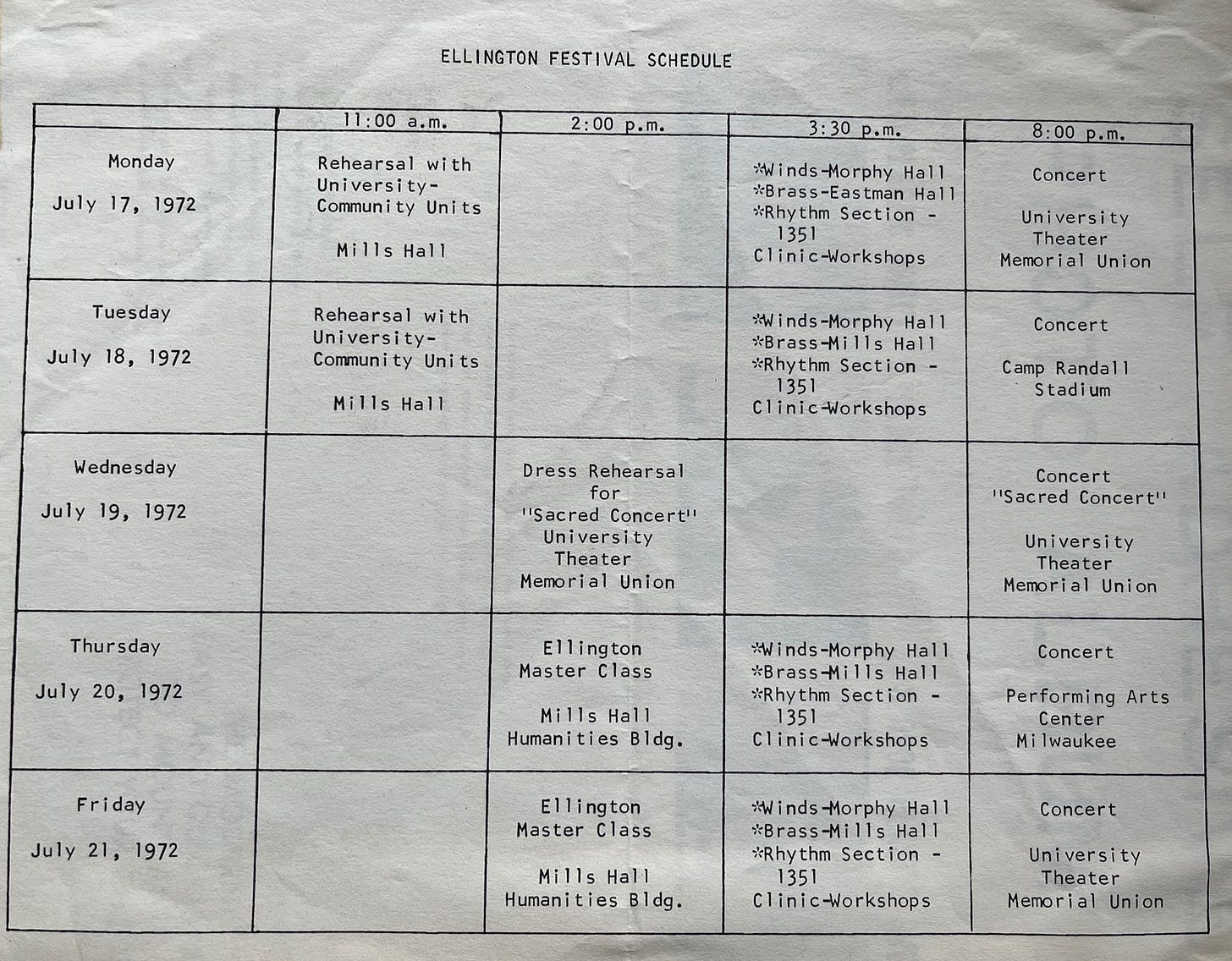

“There were brass classes and whatever. These were work days for me and so I elected to skip work on the two days that Duke was having master classes.”

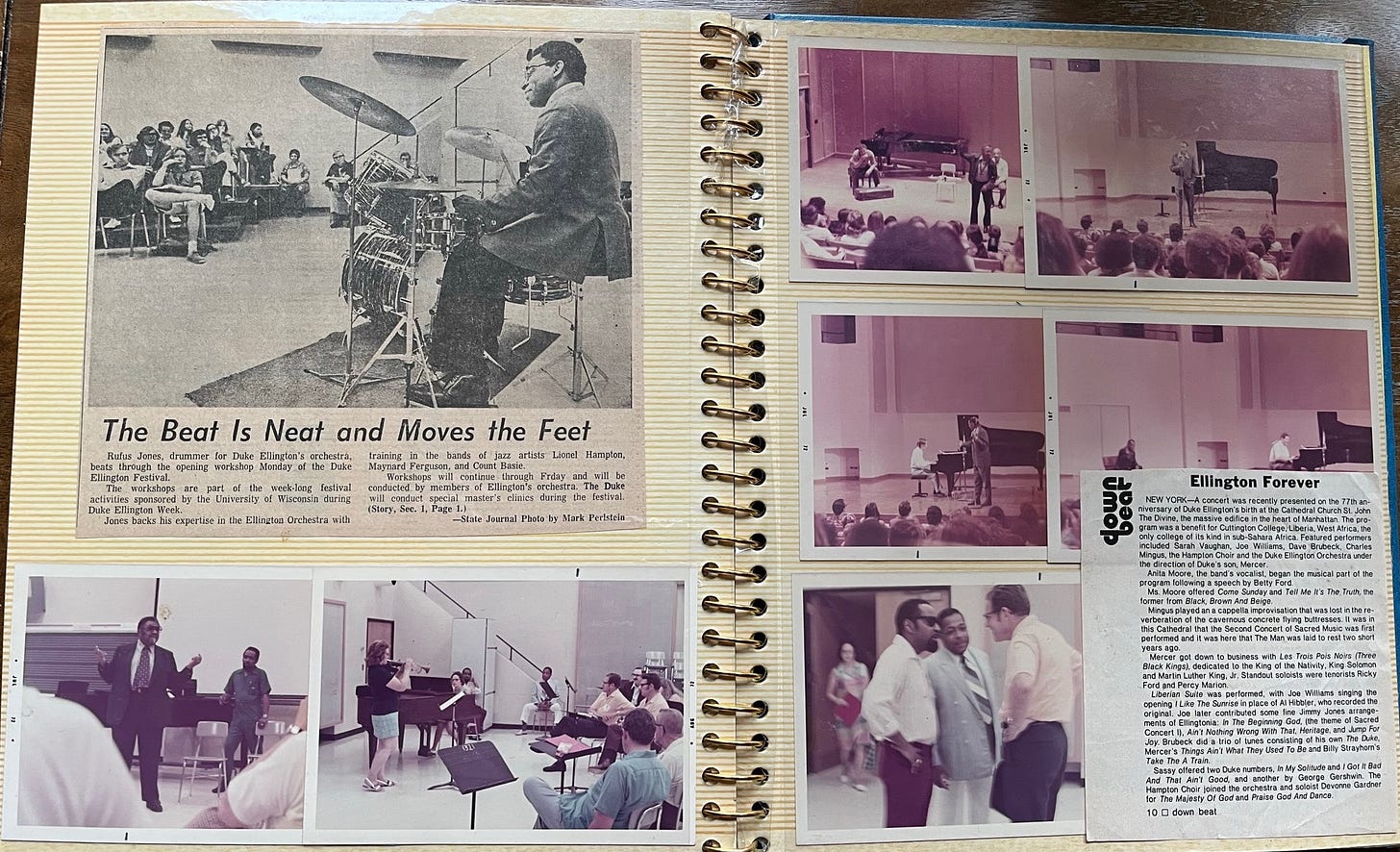

With his extensive knowledge of jazz, his work with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, for example, coming out of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), what was Chuck’s assessment of the 1972 iteration of the Duke Ellington Orchestra? “It was just different in some capacities,” he argues. “It was probably a little weaker but it was still an Ellington.”

And the Sacred Music? For many jazz fans and the most ardent of Ellington admirers, his sacred music remains difficult to reconcile with the rest of his corpus. Chuck says, “It worked fine. I mean the fact it’s basically Ellington interested me. It was just another aspect of Ellington.”

In fact the presentation of Ellington’s sacred music during the course of the festivities was an aspect Chuck Nessa found particularly striking.

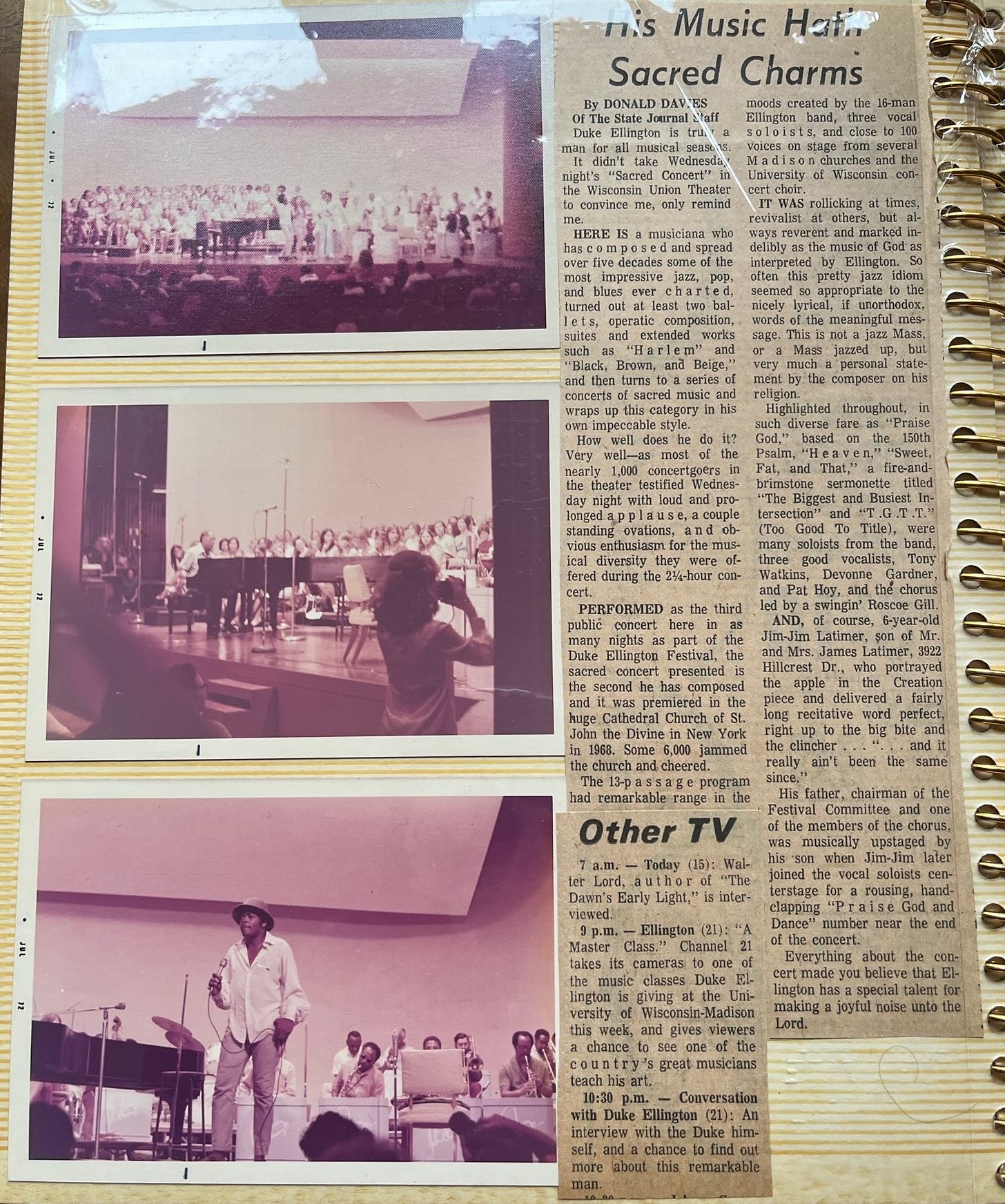

“The most spectacular of course was the sacred music concert because it was very visual. When I went to pick up the tickets at the box office that night Patricia Willard was there waiting for me and said ‘I’ll escort you to your seat’ and we went down to the front. We were in row 2 right in the centre in front of Ellington. When he came out, he bowed to us and there were dancers and a chorus and singers. It was really a spectacle.”

The best, however, was yet to come:

“After the concert, we were ushered backstage to see Ellington. He was lounging in a silk robe and he was just a very gracious host. He asked me why we’d never met. My record store had a huge window display of Ellington records. Probably I brought everything into the store I could find from Europe and whatever. Some of the band members were coming into the store and shopping so he asked me why. He said, ‘Surely you’ve been where I was to see us before. Why have you never introduced yourself?’ So I said, ‘Well, I never like to bother people when they’re working’ and I’m not sure if he called me a fool or said that I was foolish but he said that I had deprived him of a friend for all these years. I’ll never forget that.”

Chuck was witness also not just to the performance of Ellington and Paul Gonsalves’ own happy reunion but Pauls’ entrance into the lecture hall.

“It was a lecture hall with the seats going up. The door at the back of the hall opened and I could hear a voice and rustling and it was Paul coming down and he was talking the whole way. I don’t know if it was unclear or what but he was muttering and talking the whole way and he was weeping and Duke welcomed him up onto the stage.”

As we can see from the video, Ellington says “Hey, Stinky, juiced again?” but the listener can hear from his voice that his previous ire is already ebbing away.

Their fates had been thankfully fused from the time Gonsalves’ incendiary 27 chorus interlude between Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue had lit up Newport some sixteen years earlier and would continue to be intertwined before being earthed at the end of their lives.

Of this performance at the end of Ellington’s workshop, it is well worth returning to Matt Lavelle’s superb description of the recording. He writes:

“If music is to convey the beauty and mystery of the human experience, then this performance can only be considered profound. Perhaps the greatest American musician in history with his number one soloist at the absolute height of their creative powers. Their bodies may have been steadily falling under the ever-oppressive weight of age, but they spent their entire lives making music to reach this level of pure expression. It’s rare to see Ellington in a duo format. With a more open rhythmic environment, Gonsalves conception comes through more than ever as he floats up and down like he’s rising above and below the surface of the ocean. He lets blues phrases jolt through him as he spirals down and cascades above. Duke provides just the right amount of conducting from the piano, instinctively knowing Paul’s moves even better than Paul himself. As my friend Eric Lawrence said, at some point in music you simply try to produce the most beautiful sound possible, and this is that moment for Paul Gonsalves. John Coltrane mentioned a core desire to focus more on making the sound itself the priority. Ornette spoke of this as well. Overall, this performance is truly beyond category, to use a favourite Ellington expression. It’s on such a high level that is transcends both in and out playing. In fact, for me this is the ultimate example of what we can achieve when we take down the walls between the straight-ahead and avant-garde camps, and just erase those proverbial lines in the sand.”

Outside of Ellington’s sacred works, I can’t think there is a better musical expression of reconciliation and absolution. Witnessing Paul’s arrival at the theatre, his descent of the steps to the stage and Ellington, Chuck Nessa says simply:

“That was just amazing to witness that and of course – I don’t know – it was just a very emotional thing.”

My thanks to Chuck for his time and invaluable reminiscences.

Until recently the video of Duke Ellington and Paul Gonsalves playing Happy Reunion was available on YouTube. That seems to be no longer the case. I have, however, uploaded the video to my own blog Ellington Live and it may be viewed at the link here:

https://ellingtonlive.blogspot.com/2022/10/happy-re-reunion.html