Tone Parallel

Issue 10 January 2024

Rainbow’s End

The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God headquarters at The Rainbow Theatre, stands at the junction of Isledon Road and Seven Sisters Road, Finsbury Park, North London. This magnificent Art Deco listed building with its Moorish interior and seating for 3 500 punters was acquired by this religious organisation of Brazilian origin for 2.35 million pounds in 1988. Opened as a picture house in 1930 called The Astoria, The Rainbow Theatre as it was later rechristened enjoyed its greatest fame as a venue for live music during the fifties and sixties, the last performance there taking place, perhaps appropriately enough on Christmas Eve, 1981.

By the time Duke Ellington and his Orchestra played The Rainbow, Finsbury Park on 3 December 1973, the theatre had certainly seen better days. The Orchestra had played there 10 years previously on the itinerary for their 1963 tour of the UK. This occasion, however, was to see the two houses that comprised Duke Ellington’s final concert in the UK. More famous as the venue for rock acts, its hallowed walls less likely to reverberate to the sounds of Frank Sinatra than Frank Zappa, it was an incongruous setting for this last performance.

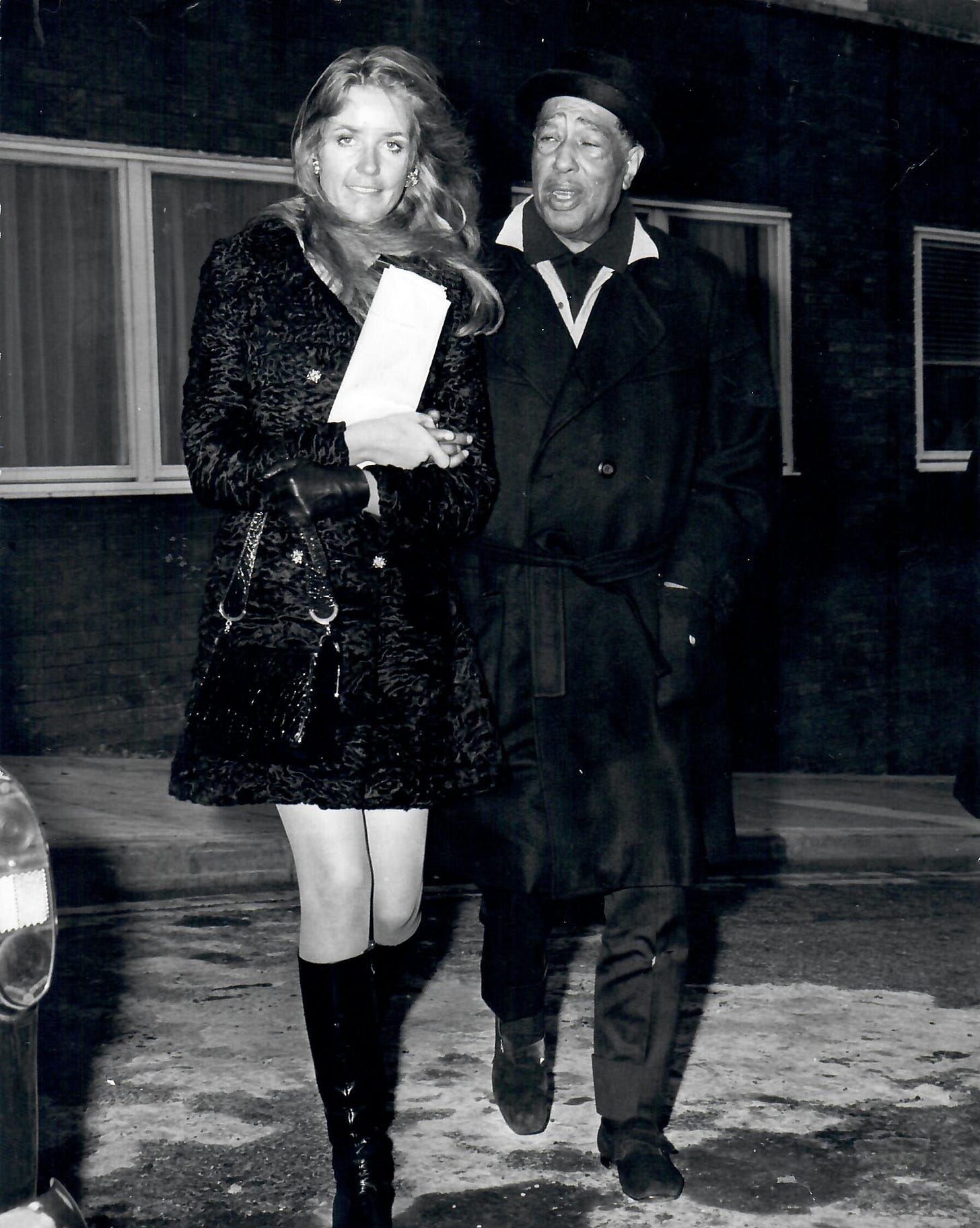

Ellington’s final tour of the UK was organized by the British impresario Robert Paterson. His wife, Sybille Baptista, is pictured with Duke in the photograph that headlines this essay. On the webpage dedicated to the memory of her husband, Sybille Baptista explains how the tour came about:

“To persuade The Duke to come to Europe, Robert and I flew to San Francisco. We were announced at the Fermont(sic?) Hotel, Duke Ellington not realizing that the wife had come as well! He opened the door of his suite draped in a towel with a turban on his head. I quickly disappeared and was allowed in a few minutes later. We all became very good friends and I accompanied Duke Ellington often on his tours, sitting in the back of the limousine and eating cold steak from a doggy bag.”

It seems that Robert Paterson also visited Ellington while he was in hospital for the last time in May of the following year. Sybille Baptista writes:

“I overheard (Robert) booking a flight to see Duke Ellington, who was in Hospital in New York, and for the first time ever I had to beg him to take me as well. I loved Duke Ellington and he was very fond of me, always asking for me when we were on tour. On one occasion at the Odeon Hammersmith Duke Ellington asked his orchestra to stand up when I entered the hall!”

In an interview on the website set up in his memory, Robert Paterson explains how he first became acquainted with Ellington:

“I was working very late in my office one hot August night – one of the few – and I had a call from Derek Jewell who was publishing director at Times Newspapers and a close friend of Duke Ellington’s. For various personal reasons, Duke Ellington had called Derek and said he wasn’t coming to Europe that year. Derek – en passant – in a moment for which I will eternally be grateful to him, suggested that Ellington contact me quarter of an hour later. Having said, yes, I’d love that, Duke called me and I’ll never forget his opening remark was ‘Hi, baby, are you feeling cool?’ to a total stranger. Two days later, I was in San Francisco in Bimbo’s club having accompanied Ellington from his hotel. He always chose hotels which had Chinese room service or room service which would put up with sending out for a Chinese meal. It was of course the days of the great band with Johnny Hodges and the front desk with people like Harry Carney, Paul Gonsalves, Lawrence Brown, Cat Anderson and, of course, Cootie Williams. I signed Ellington for a European tour which happened in ’69 and I was fortunate enough in that he let me become a very close personal friend of his.”

Bimbo’s Club and the Fairmont Hotel, San Francisco are significant locations for Ellington in 1969: it was here that he first encountered also Betty McGettigan about whom we have learned in previous editions of Tone parallel and to whose story we will return later this year.

In his reminiscing, Paterson turns subsequently to Ellington’s final tour of the UK and his last days upon his return to the USA:

“I was heartbroken when I was in Los Angeles and had a call from (Ellington’s) sister (Ruth) to say that he was dying and wanted to see me in hospital and in fact two days before he died, Andy Williams was back in England for me… (Duke) was allowed three phone calls that day, it was his seventy-fifth birthday, April 29th 1973 (sic). One was from President Nixon who was then in office; one was from Rockefeller and one was a combined call from Andy Williams Michel Legrand and I from the artists’ room at the Albert Hall and he sounded very sick. I went over to the funeral and looked after the family as much as one could and took Count Basie and Benny Goodman to the funeral and even people like Judy Collins who musically were so affected by his death. It was really a state funeral. There were 65 cars in the cortège that went for an hour and a half at very slow pace through the streets of New York and made stops outside Ellington’s first house in Harlem, the old Cotton Club, the old Roxy Theatre. We stopped in silence for a minute and I was in the third car and it was one of the most profound and moving moments I think of my life. It was quite extraordinary going through Harlem with all the shuttered windows and everybody standing in silent homage in the streets.

“The great thing about Ellington was that he had, up to about 1971, he had almost a constant band for forty years. Johnny Hodges died and then of course Paul Gonsalves died tragically in England and Harry Carney’s now gone and Joe Benjamin was killed in a car crash and slowly the band… Curiously as Duke became sicker, members of the band died. The whole thing began to disintegrate at once but Ellington was able to write a piece of music one night in an airport lounge and hear it performed the next night because the band was an extension of his whole being. I mean he just had to give them the dots…’

Paterson shows here his close association with Ellington’s music and an insightful understanding of what one might almost term the symbiosis that existed between the composer and his orchestra.

The interview extract closes with a notable claim by the promoter. I was unaware of his professional association with Ellington extending to his involvement with production of the albums and am at a loss to account for the way in which Paterson might have been involved in apparently half a dozen of his records. Paterson says:

“I used to always ask him to play as an encore, and bless his heart he usually did, that beautiful, beautiful piano solo called Lotus Blossom, which in fact Billy Strayhorn wrote. I was fortunate enough to make the last six albums with Ellington and on one of them he included as a favour Lotus Blossom and that certainly was my favourite piano solo.”

It appears upon closer scrutiny of discographies of the recordings of Ellington performances we know about, Paterson’s claim to have instituted the custom of the programme being rounded off with a performance of Lotus Blossom is not without some merit. It would indeed appear to be the case that Strayhorn’s transcendent composition did begin to appear as a regular encore following Ellington’s European tour of 1971 with which Paterson certainly as involved.

And it is absolutely beyond doubt that for the second and final house at The Rainbow Theatre, the evening’s entertainment concluded with Lotus Blossom.

This was not the final performance of Lotus Blossom Ellington gave in the UK; that honour goes to the rendition he played the next day at Lime Grove Studios, London for a pre-recorded BBC telecast. It was Ellington’s final performance on British soil in concert, however, before a paying audience.

The recording that follows is of that performance at The Rainbow Theatre. Audio quality is just about listenable but any shortcomings on its sonic fidelity are more than made up for by the fact that we can hear this last performance at all. It exists due to a bootlegged recording made by a member of the audience in the auditorium. To add an extra layer of poignancy to the occasion, we hear the voice – possibly of the man who made the recording – talking with his companion. As the audience applauds this final rendition to the very echo, it becomes apparent that the show is over. Our man turns to his companion and can clearly be heard saying:

“I thought there might not be another interval… no looks like they’re coming off. Yeah, that’s your lot.”

*

More music and stories from The Rainbow Theatre, Finsbury Park, 1973 in the final part of this essay in the next Tone Parallel.