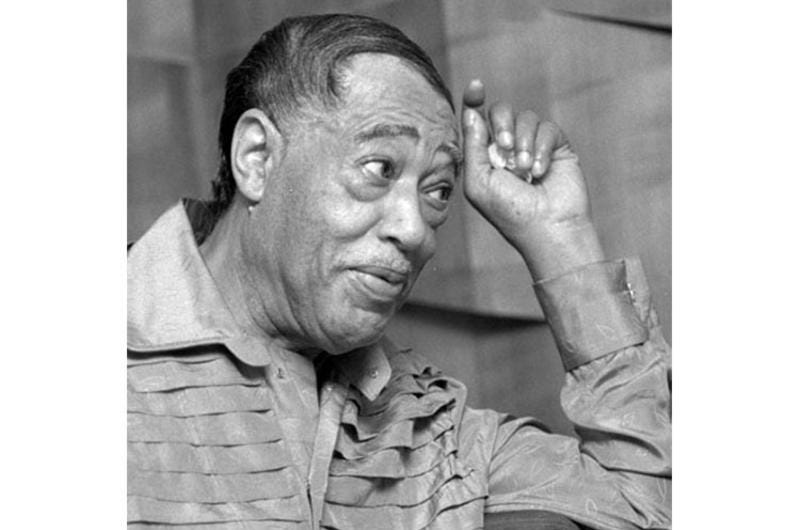

To misquote a well-known aphorism about his music, Duke Ellington plays the piano but his instrument is the telephone.

The intimates of Ellington’s world could expect a call at any time of the day or night, depending upon where he was and how pressing his needs. Ellington aficionado and collector Jerry Valburn, for example, recalled how Ellington rang him in the small hours when Valburn had long been asleep in bed in order to identify a tune that turned out to be Billy Strayhorn’s Raincheck. On another occasion, Ellington, in England at the time on a European tour, requested that Valburn send him a copy of a recording of Night Creature that Valburn had made in performance in 1956. From that tape, Ellington and Strayhorn re-orchestrated the entire piece for sessions on the continent that comprised the album The Symphonic Ellington.

It was the commissioning of another symphonic piece that caused Ellington to ring the home of world-famous plastic surgeon Dr. Bernard L. Kaye in 1972 when the phone was answered by his young daughter, Deborah.

I had the pleasure of talking recently about this occasion courtesy of the technological marvel that is Zoom, to Deborah Hollis Kaye, now retired from being a Senior Managing Attorney at one of the world’s largest financial institutions, who still works and lives in New York City. She told me:

‘I was a child at the time… We knew that the Duke was going to call, and I think that symphony was supposed to be in May, but the call was months and months before that. We knew the date and time that he was going to call. We were all sitting around waiting to pick up the phone. The call didn’t happen at the time we scheduled, so we were getting worried it wouldn’t happen, and we were becoming frantic – maybe we screwed up the date and time? At last, the phone rang. It was a battle in the family to get to the phone first, but I won so I answered and said,“Dr. Kaye’s residence,” because we were hyperventilating, trying to keep Dad calm waiting for all this call. (Ellington) had this fabulous voice. It was what you might expect. It was very deep and sonorous. It kind of filled the whole scope of (the phone). “Hullo is Dr. Kaye there?”

I was trained to say, “May I ask who’s calling- (you, know, in case of medical emergencies)?”

“Duke.”’

Why was Ellington calling the home of a renowned plastic surgeon, author of works such as Facial Rejuvenative: A Color Photographic Atlas?

Ellington had been commissioned to write a symphony celebrating the 150th anniversary of the founding of Jacksonville on the Atlantic coast of Florida. The Jacksonville Symphony Orchestra included amateur musicians, the most distinguished of whom was Dr. Kaye. Deborah told me:

‘My father… I didn’t think to ask when he started playing but he played a variety of wind instruments and other esoteric things. You name it, he probably could play it. He was remarkable in that sense and our house was filled with music. Every room we had a different type of music going. My mother loved opera. My brother also plays multiple instruments. I was more the physical dancer type although I dabbled a little piano and flute. We had in the living room our musical museum place. We had two baby grands back-to-back and we had a music cabinet that was custom made - probably twenty feet long and eight or ten feet high and we had every possible saxophone and flute and clarinet… Years later, when I became a world traveller, every country I went to I picked up a musical instrument… I was lucky enough to go to the Peoples Republic of China in 1976 right after Nixon went, so I bought an erhu and all kinds of crazy things around the world. People would come into the living room and the first thing you saw was this music cabinet with everything that dad would play. The family would get together, and we’d have impromptu concerts for ourselves. My father would either get on the piano and I would get on the other piano and my twin brother Robert would get on the bass or drums or something. My father also played the bagpipes, my brother played the bass drums and I would do the sword dance this was crazy it was not your normal childhood. We performed in a Scottish Band for family fun.

‘When we jammed, dad would walk up to the cabinet and decide what was called for. I think he also met Tito Puente at one point and he also played with a couple of the early famous jazz bands when he was a kid out on Glen Island here in New York because he grew up in New Haven so for him playing for Duke it was like arguing for the US Supreme Court.’

Dr. Kaye’s fame went before him. As Deborah explained to me:

‘What would happen is that because my dad was the plastic surgeon and sort of famous, if there were a chance for a solo then a lot of people would come to more of the concerts, then they would publish in the paper: “Local surgeon plays a solo role.”He would solo for things that have a great flute, saxophone or clarinet piece and they’d make more money.’

Ellington must therefore have been asked in the initial commission to incorporate a solo for Dr. Kaye’s particular talents. But Ellington had to know what to write for, the tone, the style. So, the call was arranged to hear him play so he could assimilate the surgeon’s tone and style into the piece he was writing.

‘When I put my dad on the phone …My dad answered,’ Deborah continued ‘and (Ellington) said, “Let me hear you blow, man,” so (my father) put down the phone, and he played a few bars and (Ellington) said “I dig it,” and hung up … and we just all stood there.’

Ellington called from Canada. When I asked Deborah Kaye the date, she remembered, ‘I vaguely remember it being kind of winter. Winter in Jacksonville wasn’t really winter; it was kind of cool out…’ We can say with some confidence that Bernard Kaye’s ‘audition’ must have taken place in March 1971, between Monday, 13th and Sunday 26th. During this time, the Orchestra was playing a two-week residency at the Beverly Hills Motor Hotel in Downsview, Ontario. Perhaps it was from the Beverly Hills, between sets or after the show, that the call came.

This is also borne out by the recollections of the man assigned the orchestration of Ellington’s symphony, Canadian Ron Collier who, while the band was in Toronto, was able initially at any rate to work on the assignment from home. Subsequently, and with the deadline to the performance in May looming ever closer, Collier was obliged to go out on the road with the band, in order to continue his orchestration. Deborah’s mother saved all the newspaper clippings surrounding the symphony, and they indicate that Duke was in fact in Toronto.

The linear, episodic structure of the symphony, which runs to about thirty minutes, is perhaps a reflection of the conditions under which Ellington and Collier were working and life on the road. Collier has stated that what Ellington provided were little more than “sketches” from which he assigned the constituent parts of the symphony orchestra. Deborah Hollis Kaye’s invaluable testimony, however, proves that this was not entirely the case. Indeed, her recollection only emphasizes the significance of this composition within Ellington’s oeuvre in terms of the instrument chosen for this solo and the working method by which Ellington scored this part of the symphony. The choice of alto saxophone is hugely significant. Whether this was Ellington’s own choice or Dr. Kaye’s or somebody from the Jacksonville Symphony, is not known. Deborah thinks it was the conductor’s choice, and slightly remembers her dad’s musings about his “alto tone” practices.

Consider, though, that Ellington never ‘replaced’ an instrumentalist from the ranks of the Orchestra. When a player left or died, Ellington never attempted to replace or replicate that musician’s sound. The loss of Johnny Hodges who had died two years earlier was particularly grievous and, in the final three years or so of the orchestra’s life, the orchestra’s repertoire on stage or the dance floor and the new pieces Ellington composed subsequently, the alto saxophone was hardly ever featured as a solo. The significance of Ellington writing for this instrument, then, in 1972 can hardly be exaggerated. Of equal importance is the fact that Ellington, the self-styled “world’s greatest listener” had taken the trouble to call and listen to the sound of the man who would be playing this solo. It was a piece of bespoke writing ensuring that Dr. Bernard L.Kaye therefore joined the ranks of a very exclusive band of musicians for whom Ellington wrote specifically, weaving the very soul of the man into the tones and textures of his composition. This was something rather more than providing Ron Collier with a ‘sketch’. The value of a recording of the première performance, of which more anon, is therefore beyond rubies.

In the video, below, which allows us to hear a snatch of the opening of the symphony but not unfortunately Dr. Kaye’s solo itself, the manuscript for Celebration can be seen. Of this manuscript, Deborah Hollis Kaye told me: ‘…you know the piece came and you know you’ve seen it. It was all scribbled cause I remember my father playing as he always did over and over and over and to get his tone. I could never hear the difference because he always sounded good.’

I am reminded of the old joke, ‘How do you get to Carnegie Hall?’

‘Practice.’

(In fact, the Jacksonville Symphony played in Carnegie Hall; Deborah recalls her father and the entire Symphony being so proud of that).

It is an arresting image to consider Dr.Kaye practising and practising to burnish his tone and prepare for the concert, the tone to which Ellington listened so carefully and sculpted into the melody of his symphony.

Bernard Kaye’s solo was also the culmination of the entire work. The programmatic nature of the piece (its ‘tone parallel’) is outlined briefly in the account which follows. Suffice it to say, and considering the symphony’s episodic nature, various motifs within the piece were given titles by Ellington. Dr.Kaye’s soli are integral to the last two movements of the piece, Ballade and the finale which gives the symphony its title, Celebration.

The première performance took place on 16 May 1972 and was attended by Ellington himself and his entourage including Stanley Dance whose own account of the occasion was published in the UK’s Jazz Journal, Volume 25, Number 7, July 1972. He wrote:

“On May 16th, the sesquincentenniel (that’s the one-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary, in case, like us, you didn’t know) of Jacksonville was observed by that city’s symphony orchestra in the handsome Civic Auditorium. Thereabouts it was that Delius settled down in Florida, and there James Weldon Johnson of the spirituals was born. Although billboards proclaimed them ecstatically, we never saw the golden beaches, because they were twenty miles away from the central hotel to which we had been summoned…

… In the climactic spot, there was Duke Ellington’s new symphonic work, Celebration. Willis Page, the conductor, had him up on stage to say a few witty, introductory words. The original notes described it as being ‘based on Mr Ellington’s memories of visits to Jacksonville. The overture recalls with melancholy the long extinct Number Two Club (sic) – a Jacksonville nightclub where blues artists used to gather for jam sessions. Moving to the core of the city, the composition builds up to a fanfare which represents the growth of Jacksonville. Turning to a romantic theme, the composition closes with a musical allegory describing that beautiful girl – Jacksonville’.

Ron Collier, who had gone ahead to help with the orchestration and, as it happened, to write parts and catch ‘flu somewhere between the beaches and the air-conditioning, told us that the symphony was not ‘fully professional.’ Perhaps the presence of enthusiastic amateurs accounted for the zeal with which the work – just under thirty minutes long – was played. We have often seen disinterested symphony professionals reading newspapers and magazines at every opportunity during rehearsals, and their subsequent performances as often reflected their attitude. Here there was real co-operation and a determination to do the best possible, which resulted in the work being played with the spirit its strongly rhythmic character required. Afterwards, the composer was obviously well pleased with the performance, and particularly with the way Page had conducted it.’ (Deborah recalls Ellington smiling.)

‘There were several attractive themes, including a very singable one for the French horns, and two high spots for soloists. The first of these, rather like Malletoba Spank, was played by the orchestra’s very capable black percussionist. The second, skilfully written in the style of Johnny Hodges, was entrusted to the alto of the city’s leading cosmetic surgeon Bernard Kaye, who gave a very creditable performance indeed with a tone that recalled those prevalent in the ’20s. Although he had boned up on Hodges’s records, he sounded more like Toby Hardwick at times.

There was a big, standing ovation, a huge reception with champagne afterwards, and a subsequent party with the mayor and leading citizens. The maestro likes to get to the place where he will next work before going to sleep, so he arranged to catch a 4.30 a.m. flight. On arrival in Atlanta, there was an hour to wait before making the connection to Dallas. When we had been made comfortable by airline officials in the V. I. P. lounge, we played the cassette recording of Celebration that we had made at his instructions. He remained alert, interested and a little amused throughout. “We stayed in Soulville a long time,” he said. “And did that saxophone solo sound like Rabbit?”’

Celebration was performed again on the occasion of Duke Ellington’s 75th birthday, 29 April 1974 at the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto. Ellington, who was in hospital at that time with his final illness, died a little over a month later. Ron Collier, who conducted the symphony orchestra on that occasion, sent Ellington a tape of the performance but unlike the recording from Jacksonville, it seems unlikely that he ever heard it.

The recording of the Jacksonville première seemed lost for many years until the efforts of Dr.Bernard Kaye’s daughter to track it down. Deborah was taking a course in the History of Jazz led by Professor David Wolfson at Hunter College, New York. Deborah told me:

‘The symphony was lost. Jacksonville didn’t even know they had this symphony. Here’s the story. I was retired and taking a music course - The History of Jazz -so when they got to Ellington I said, “I have this piece with a solo by my Dad, and I will bring it to class.” I said, “I’ll play it for you” and so I looked in my files and I knew I had a little tape, but I couldn’t find it. I called Jacksonville to ask them for a copy, but they didn’t even know what we were talking about. I told them everything. So,I said, “I’ll find it for you,” and that was when they told me they were entering a competition against local symphonies around the US. The winner would play in Kennedy Center, and receive a grant from Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. “Huh”, I thought. “Could be cool if they played this.”

‘I couldn’t find my tape; I hadn’t talked to my twin brother in years, but I knew he would have it, so I called him, and he said, “Sure. What form do you want it in?”- leave it to him to have everything! My stepmother had saved all the newspaper clippings that my late mother had, so she sent them to me. I called the head of the Jacksonville Symphony and told them I found everything about the work, my dad’s solo. We talked about the Kennedy Center contest and grant, and that they didn’t know what to play. It ended up that they amended their contest and grant piece to play Celebration. To my surprise and delight (and surely dad’s), they won. It was really stunning.’ Deborah donated a copy of everything to Hunter College for posterity as well.

The Jacksonville Symphony intended to play Celebration in March 2020 but the performance had unfortunately to be cancelled due to COVID restrictions.

The reputation of Ellington’s ‘lost’ symphony continues to grow, however and a version of the symphony was recorded in 2018 by Orchestra del Teatro Marrucino directed by Bruno Tommaso to accompany the book Dalla Scala a Harlem, a study of Ellington’s symphonic works, written by Luca Bragalini, Professor of Jazz History at the Music Conservatory of Brescia, Italy. Currently, the book is only available in Italian but an English translation has been commissioned by the International Center for American Music. The translation has been completed and we await publication of the English version eagerly.

Of the occasion when she spoke with Duke Ellington over the phone and her father’s work with Ellington, Deborah Hollis Kaye said:

‘It was one of these remarkable moments in my life. When we got to Jacksonville frankly I just hated it because I’d come from the north and you know the weather, mosquitoes… The one thing (was) that the flora and the vegetation were good and my Dad’s access to playing was good. One thing he used to do was something called The Twilight Symphonette and you know in the summer they used to play outdoors. Most people, adults, would love it of course. We as little kids, it was hot. Dad loved it because he could play everything that he ever knew how to play in this wonderful outdoor concert in the evening and you know… the sun was setting and this beautiful location which of course as kids we didn’t appreciate. Now I would be, “Oh, man, this is great”… They played everything. He got to solo and they were always sold out. It was beautiful. I don’t know, but I can’t imagine they didn’t have him play (Celebration) again…’

There can be little doubt that this remarkable piece of music, and Deborah Hollis Kaye’s equally remarkable story will certainly live on.

Many thanks to Deborah – and her brother Robert Kaye - for their kindness and generosity in sharing their memories.