Tone Parallel

Issue 15 December 2024

In her interview with Vivian Perlis as part of the Oral History of American Music project at Yale Library, which took place in New York City on 16 July 1980, Betty McGettigan spoke of Duke Ellington’s affinity with language:

“He was so much a man of words. He loved words. I’d say… what? … about three, four dictionaries and a thesaurus…

“We’d just go through words and all kinds of things. He loved words and he tried to find all these different words for one thing and words that would go together I mean you know words were in his...”

Vivian Perlis responds: “That’s very interesting his (interest) certainly showed… I mean everybody knows the way of way of expressing himself was extraordinary but the fact that he actually worked at it …”

“That didn’t just come out you know,” McGettigan replies, “… flow out from some little river inside of his head. Part of it did…”

It is a significant exchange, bringing into focus as it does Ellington the librettist. Vivian Perlis notes that Ellington was renowned for the loquacious nature of his stage patter but finds Ellington’s engagement with linguistics (what she calls “a real interest in according to where words came from and what other meanings would be and all that…”) something of a revelation.

We see evidence of what Ellington might well have called his “lexical calisthenics” in the documentation preserved in the Betty McGettigan Collection held by the Smithsonian Institution. On one piece of notepaper, for example, Ellington had written “eiffedience (sic) of ingredients plus obedience results in suceedience (sic)”.

This confection is characteristic of the ‘patois’ Ellington employed in both his stage announcements and in his work on lyrics and libretti. It is perhaps worth remarking that the authority with which his assertions stand is less a matter of semantics than sonics. Some of these aphorisms may, in semantic terms, be quite nonsensical with made up words but their authority rests, rather, in the fact that they rhyme.

Besides being light, inconsequential and often mischievous statements, however, Ellington’s idiosyncratic syntactical constructions can bear the weight of rather more serious even somber pronouncements, more characteristic of the libretto of one of his Sacred Concerts. Consider these lines, for example, by Ellington jotted on a piece of notepaper:

Are you doing the right wrong?

Or are you doing the wrong right?

Are you righting the right wrong?

Or are you wronging the right you?

The technique of inversion, synthesis and antithesis is similar to Ellington’s more frivolous epigrams but the tone is markedly different.

Typically, too, these squibs were usually to be found on a piece of hotel stationery. Libretti and lyrics alike for both The Third Sacred Concert and Queenie Pie were scattered throughout Ellington’s papers. Clearly, he was working on these two last major presentations concurrently. To these two, we add another major composition which required neither libretto nor lyrics, Les Trois Rois Noir. Together these works comprise a trifecta of Ellington’s final artistic statement on race, love and mortality, the trinity which it could be argued informs his entire body of work.

With regard to his work as a writer, the fact that many of his lyrics were jotted down initially on hotel paper, we may hazard a guess at the point in time in which they were created by examining Ellington’s itinerary. Ellington famously remarked, “We don’t do tours”. He was on the road seven days a week, fifty-two weeks a year. We can therefore pinpoint his location, in both space and time when these lyrics were written with some accuracy.

The lyrics to the composition Second Line, destined to be included in Queenie Pie are a case in point.

Second Line was a composition written for Ellington’s appearance at The New Orleans Jazz Festival that took place on 25 April 1970. Five days earlier, the Ellington Orchestra had been enjoying a residency at Al Hirt’s Club on Bourbon Street. It was at this location, on 23 April that Ellington ran down this new chart and it was recorded in studio on 27 April when the band had returned to New York. A second studio recording for Ellington’s ‘stockpile’ was made in Milan, Italy, on 23 July that year. There are a further 30 recordings extant of the piece being performed in concert. It remained in the book until at least 11 February, 1972 when it was performed in concert in Sydney, Australia.

The piece was therefore one to which Ellington returned frequently and the last known recorded performance brings us almost to within twelve months of its inclusion in the score of Queenie Pie.

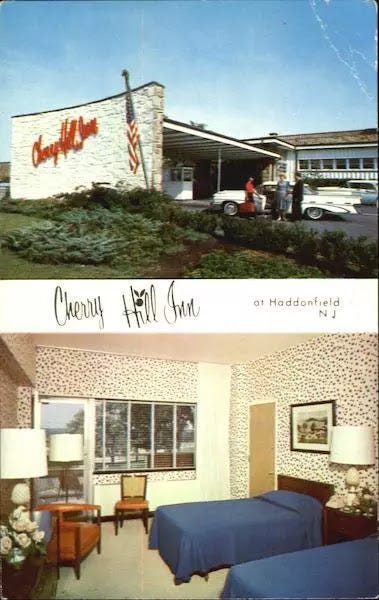

The late summer of 1973 seems to have been a particularly crucial time in the chequered history of the street opera. In early August of that year, Ellington was in New Jersey for two days. 4 August found him in Cherry Hill. Is it too fanciful therefore to suppose that the lyrics for Second Line were set down on this date? The lyrics appear, in Ellington’s own hand on a piece of hotel stationery emblazoned with the logo of Cherry Hill Inn, Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

According to John Franceschina in his book Duke Ellington’s Music for the Theatre, WNET, the public broadcast television station in New York which had commissioned Queenie Pie, cancelled the project following a presentation by Ellington in June 1973. The assumption that the lyrics to Second Line were indeed jotted on the Cherry Hill Inn notepaper in August of that year is corroborated by the fact that a manuscript exists which outlines the opera and is dated 31 August 1973.

It would seem that the cancellation by WNET only inspired a frenetic burst of activity on Ellington’s behalf, his ambition to turn the hour-long television broadcast (an uncanny echo of the format for A Drum Is A Woman the better part of twenty years earlier) into a fully-fledged ‘street opera’. Was Second Line included in the June presentation to the WNET executives or were the lyrics freshly minted in Ellington’s room at the Cherry Hill Inn?

Written by hand, we can assume the lyrics were Ellington’s own. The lyrics comprise a list of declarative statements alternating with injunctions simply to join in:

Unwind and get behind that Second Line

Sashay and balancé on Second Line

And play and sway all day on Second Line.

Whether intentionally or not, much of the import of the lyric, and particularly the assertion that “From nine to ninety nine/ they’re superfine” is reminiscent of the style of commercial advertising which, as we shall examine later, plays a significant part in Queenie Pie.

As with many of Ellington’s aphorisms, it is both rhyme and, of course, here the melody which carries the piece rather than any inherent value in the lyric itself. It serves its purpose, introducing to the stage the character of Queenie Pie’s rival for the crown, Café Olay, the Queen of New Orleans. New Orleans has come to New York.

Second Line is an invitation to “follow the band”, to enjoy the music and the dance in a Bourbon Street parade. In order to remain alive to the social and economic undercurrents of Ellington’s work, it is helpful to note that these parades were organized by the Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs of Louisiana. They are what Dan Baum called “a jazz funeral without a body”. It is a tradition – perhaps, more accurately, a ritual – which owes its origin to enslaved Africans. It is the music of Congo Square and another connection to the continuum that exists between Boola, Black, Brown and Beige and A Drum Is A Woman. In its social dimension, where the SAPCs assisted their members through financial difficulties because they could not procure insurance from white insurance companies, it has echoes too of Ellington’s charting a private Pullman car to tour the south in the late thirties. As Ellington observed, “You’ve got to find a way of saying it without saying it.”